Filter, September 25, 2018.

© Copyright 2018 Stanton Peele. All rights reserved.

In 2018, the Temperance Movement Still Grips America

Stanton Peele

Our society—even some of its most progressive elements—vilifies alcohol. This stands in opposition to public health, enables government suppression of lifesaving information, and encourages anti-substance-use attitudes across the board. Yet it typically goes unchallenged.

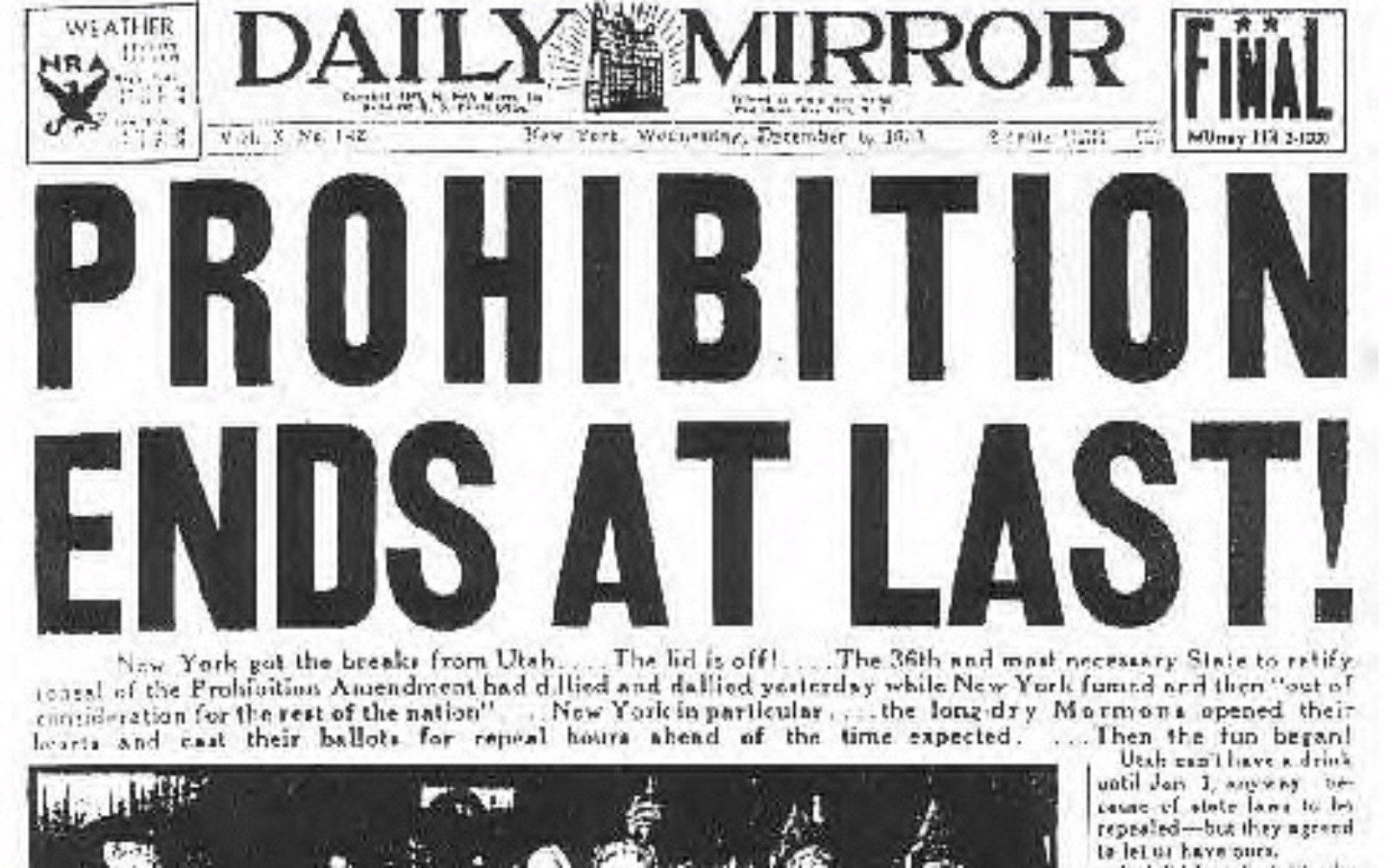

Temperance—the Protestant vision that alcohol inevitably causes uncontrollable psychological, spiritual and physical ruin—originated with the “Gin Craze” of 18th-century England. The Temperance Movement gained peak traction in 19th-century America, ultimately prompting Prohibition in 1920.

But Repeal didn’t end our Temperance culture. For one thing, Alcoholics Anonymous, with its abstinence-only approach, quickly formed in its aftermath. Americans are still likelier than inhabitants of other rich Western nations to abstain from alcohol. Dry jurisdictions still proliferate in the South, and not just there. Restrictions on sales and consumption abound: The United States is the only Western country with a legal drinking age of 21.

We might primarily associate Temperance with conservative regions and politicians; our current President, of course, is teetotal. But Temperance attitudes are embedded across political lines.

Lessons From the World

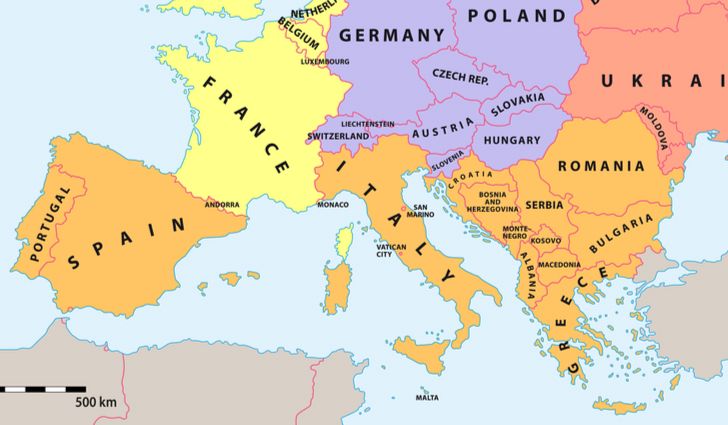

Our Temperance battle has echoes worldwide. In the international version of this dispute—one in which I have played a vociferous, if probably inconsequential, role—Northern European, Temperance-culture epidemiologists attack alcohol consumption. They have succeeded in imposing formal controls on alcohol, most notably raising the drinking age in Southern European countries—ones that cross-national studies show have fewer alcohol problems than the Temperance nations that dictate international health regulations.

The global public health establishment supports these efforts: The latest in a series of global studies claiming alcohol’s effects to be solely and totally deleterious—widely trumpeted in the world’s media—calculates the optimal level of drinking to be exactly zero.

In fact, comparisons within and among Western nations overwhelmingly find drinkers to be healthier and to live longer than abstainers, even when research controls for potentially confounding factors. (I review some of the research in this article for Filter.)

Non-Temperance cultures—notably in Mediterranean countries like Greece, Spain, Portugal, Italy and France—view alcohol, consumed mainly in wine, as a natural, healthy food product. Alcohol is seen as an essential accompaniment of good times at social and family gatherings, where its use is subject to strict, if informal, social controls. Due to this cultural approach, drinking ages are lower in Mediterranean countries—traditionally 16, though even this limit is generally not observed. Yet Southern European youths display fewer drinking problems.

Looking north across Europe, through countries that impose greater formal controls on alcohol, we see a striking rise in both alcohol-related social problems and medical ones, such as cirrhosis. Alcohol-related mortality is higher in Temperance than in Non-Temperance countries—even though Non-Temperance countries consume more alcohol.* The US shows a similar inverse correlation between states’ health status and per-capita alcohol consumed, whereby higher alcohol-consumption states are healthier.**

How can this be? The answer lies in different drinking patterns learned early in life. In Mediterranean countries, first alcohol use typically occurs at a young age—so young, most can’t remember the first time they drank—at multi-generational mealtime gatherings.

In Northern Europe, first use typically takes place during illicit binge-drinking sessions with teenage peers. The practice of drinking large amounts in a short period of time, often in single-generation, single-gender groups, is ingrained, with resulting social and health problems.

Those of us who recognize these disparities take a keen interest in the work of investigators who, on discovering fermentation and consumption in the archeological record of every one of the global birthplaces of civilization, assert that human reactions to the ethanol molecule are encoded in our DNA. In his 2009 book Uncorking the Past, bioarcheologist Patrick McGovern argues that alcohol spurred human civilization by prompting grain cultivation, as well as facilitating social interaction and expanding human consciousness and creativity.

Progressives’ Attacks on Alcohol

What are we to make, then, of the disdain for alcohol exhibited by many American liberals—those whose attitudes are supposed to exemplify tolerance and respect for evidence?

This often applies whether they drink it themselves or not. Ultra-liberal New York Times political columnist Frank Bruni pointedly noted that he wasn’t “about to abandon my white Burgundy or gin martinis.” Yet he at the same time demonized alcohol along with drugs. Liberal Joe Biden, on the other hand, is a lifelong abstainer: “There are enough alcoholics in my family.” But, like Bruni, he detests drugs and has devoted his career to fighting the addiction he believes they inevitably cause.

This summer, continuing in this Temperance vein, a highly publicized article in America’s leading progressive magazine, Mother Jones, posed the question, “Did Drinking Give Me Breast Cancer?” The author, Stephanie Mencimer, strongly suggests that it did. As a result, falling short of calling for a ban on alcohol, she recommends every policy to discourage its use:

“…higher excise taxes, limits on the number of outlets selling alcohol in a particular area, stricter enforcement of underage drinking laws, and caps on the numbers of days and hours when alcohol can be sold.”

Underlining Mencimer’s argument is the idea expressed in the subtitle of the piece: “The science on the link [between drinking and breast cancer] is clear, but the alcohol industry has worked hard to downplay it.” The industry, she argues, does this with the complicity of researchers, public health advocates, and the government itself.

Despite reviewing selected data and science on alcohol’s effects on cancer, health, and longevity (which I address more fully here), the Mother Jones article is above all a political piece. It treats us to the ungainly sight of a leading progressive magazine endorsing the alcohol control policies enforced by perhaps the reddest state in the union:

“Researchers suspect the low overall rate of breast cancer in Utah has to do with the LDS church’s strict control over state alcohol policy. Gentiles, as we non-Mormons are called, grouse mightily over the watery 3.2 percent beer sold in Utah supermarkets, the high price of vodka sold exclusively in state-run liquor stores, and the infamous ‘Zion Curtain,’ a barrier that restaurants were until recently required to install to shield kids from seeing drinks poured. Yet all those restrictions on booze seem to make people in Utah healthier, Mormon or not, especially when it comes to breast cancer.” (My emphasis.)

Utah stands out as the single great exception to the inverse relation between health and per capita alcohol consumption in the U.S.** Taking it to prove the benefits of enforced abstemiousness is therefore dangerous; Utah is an atypical state in many ways beyond its alcohol policies.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. and worldwide, the life expectancy gap is widening between the least and best educated and well-off. Much else obviously goes into this gap, but one factor is drinking. Per Gallup, “Eight in 10 upper-income Americans, college grads drink alcohol (while) about half of lower-income Americans drink.”

The US Government Buries the Benefits of Drinking

Mencimer takes special aim at reams of research, much of it government-sponsored, that has found alcohol conveys significant, life-giving benefits. The U.S. government, she argues, along with American public health agencies, has short-shrifted the dangers of alcohol while overhyping its advantages.

She cites one critical example of this “bias”: the apparent failure of researchers to realize that many abstainers quit drinking because they have poor health—leading, she claims, to the incorrect supposition that abstinence causes poor health.

I will review the evidence for and against this claim in more detail; for now, let’s focus on the big picture.

The primary benefit from beverage alcohol that has repeatedly been found is that it reduces heart disease (and other cardiovascular diseases, such as stroke). As soon as systematic research on drinking in natural populations commenced, the cardiovascular benefits of alcohol were identified. And as soon as these heart benefits were identified, the government suppressed them.

It’s just the sort of government of censorship that, in other circumstances, Mother Jones would be all over.

The most famous heart research project ever conducted is the Framingham Heart Study. Since 1948, Framingham has been tracing the heart health of the residents of this Massachusetts community across three generations; in 2002, after more than half a century of research, the Framingham Study concluded (as reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine):

“After adjustment for multiple confounders [i.e., variables other than the simple act of consuming alcohol were calculated and controlled for] risk for congestive heart failure was lower among men at all levels of alcohol consumption compared with men who consumed less than 1 drink/wk.”

The lowest rate for heart failure was among men consuming 8-14 drinks a week. For women, this amount was 3-7 drinks a week. However, when additional predictors of heart failure were taken into account by the researchers, the reduction in heart attacks for women, while still present, “was no longer statistically significant.” This latter finding itself is exceptional in support of Mencimer’s argument. Despite it, the Framingham researchers concluded overall:

“In the community, alcohol consumption is not associated with increased risk for congestive heart failure, even among heavy drinkers (more than 15 drinks weekly for men and 8 for women). To the contrary, when consumed in moderation, alcohol appears to protect against congestive heart failure.”

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in America, for men and for women, and kills far more of us than all the alcohol-related cancers combined. Drinking—despite the fact that alcohol is in some degree carcinogenic—will, on average, make both women and men live longer.

This is a conclusion reached by virtually all well-controlled research in the United States or wealthy nations at large (again, I review these results here), often despite the intentions and hypotheses of the authors of this research.

The Harvard Health Blog gingerly admitted to this imbalance between alcohol’s cancer dangers and its health benefits. Noting that “about 4% of cancer deaths worldwide are related to alcohol use,” while “compared to people who didn’t drink alcohol, those who were moderate drinkers had a 29% lower risk of being diagnosed with coronary artery disease and 25% lower risk of dying from a heart attack,” the Health Blog concluded that—even for those women at increased risk of breast cancer—alcohol is potentially healthy.

“The issue of whether or not to drink alcohol can be a very tricky one for a woman at higher than average risk of breast cancer or one worried about developing breast cancer. Not drinking would eliminate one possible contributor to breast cancer risk. At the same time, heart disease is more common and deadly among women than breast cancer. An increased heart disease risk might tilt the balance toward moderate alcohol use.” (My emphasis)

You would be unlikely to hear about the elements in this balancing act (i.e., the heart benefits of alcohol) from public presentations of the Framingham Study, however. The government, having created and funded the Framingham study, has consistently censored this aspect of its results.

That statement is based on the revelations of an early Framingham researcher, epidemiologist Carl Selzer. In 1996, Selzer wrote a tell-all article in which he described how, when he and his colleagues announced in 1972 to their government sponsor that alcohol conveyed heart-protective benefits, “they were forbidden to publish them.”

A government memo informed the researchers:

“An article which openly invites the encouragement of undertaking drinking with the implication of preventing coronary heart disease would be scientifically misleading and socially undesirable in view of the major health problem of alcoholism that already exists in the country.”

Indeed, public health officials and the government maintain more or less that same position today: i.e., the heart benefits of alcohol cannot be discussed. In 2007, Larry King hosted a two-hour PBS special, The Hidden Epidemic: Heart Disease in America, about the landmark Framingham study. In a discussion with a panel of experts about the heart effects of diet, sex, exercise and smoking, drinking was never mentioned—despite the heart-beneficial results the Framingham researchers had found.

In Temperance America, adults can’t be trusted to handle such information.

The Framingham study isn’t an isolated example. Another public venue in which the government has fought against citing alcohol’s benefits is the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, published every five years by the US Departments of Agriculture, and Health and Human Services.

The 1990 Guidelines informed Americans that alcohol “has no net health benefit, is linked with many health problems, is the cause of many accidents and can lead to addiction. Its consumption is not recommended.”

Relentless research results, which the Harvard Health Blog described in 2013 as “84 of the best studies looking at the alcohol and heart connection including more than two million men and women,” forced a modest restatement in the 1995 Guidelines. These guidelines grudgingly admitted—surrounded by warnings about the dangers of drinking—that “alcoholic beverages have been used to enhance the enjoyment of meals by many societies throughout human history” and that “current evidence suggests that moderate drinking is associated with a lower risk for coronary heart disease in some individuals.”

Even this modest statement caused a firestorm of opposition, led by the late Sen. Strom Thurmond. Thurmond, who had spearheaded warning labels on alcohol, was reported to be “absolutely furious” at the suggestion that the government would puts its imprimatur on alcohol’s benefits. (Of course, it remains unlawful to mention such benefits in alcohol advertising or labels.) But worse was to come.

The 2010 Guidelines commissioned a distinguished panel to evaluate the evidence on alcohol. Headed by Eric Rimm, co-director of Harvard Medical School’s Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, it found “strong evidence” that “the lowest mortality risk for men and women [occurs] at the average level of one to two drinks per day. . .likely due to the protective effects of moderate alcohol consumption on CHD [coronary heart disease], diabetes and ischemic stroke.” The committee added, “Moderate evidence suggests that compared to non-drinkers, individuals who drink moderately have a slower cognitive decline with age.”

A modified version of these benefits was included. But, even so, the published Guidelines continued to devote by far the greater amount of space to portraying the negative effects of alcohol. Before this finalized version, the proposed inclusion of any health benefits from alcohol was debated in the Federal Register, where it aroused the ire of public health and alcoholism professionals, who argued it would “encourage greater daily consumption of alcohol, discourage appropriate caution about using alcohol for health benefits, and open the door for the alcohol industry to misrepresent federal alcohol consumption guidelines to consumers.”

With Alcohol, Liberals Lose Sight of Their Principles

Strom Thurmond, a teetotaler who spurred early opposition to any Dietary Guidelines positivity about alcohol, was a Republican from deep-red South Carolina. Red states, like Utah, are more Temperance-oriented. So Thurmond’s objections fit the man and his background.

But isn’t it surprising to find Mother Jones in bed with Strom Thurmond and socially conservative Utah? There’s a seeming anomaly in Mother Jones’ attitudes toward the ready suppression of this intoxicant, given that publication’s staunch support for marijuana legalization.

There’s another basic contradiction in the article’s bouquets towards Utah’s alcohol policies. The author, whose breast cancer is the basis for the article, writes: “I was born and raised in Utah, and after my cancer diagnosis, I wondered what would have happened if I’d stayed put.”

And yet, here is her description of her formative drinking experiences:

“I’ve never drunk as heavily as I did before I could legally buy a drink. My experience isn’t unusual. Ninety percent of alcohol consumption by underage Americans is binge drinking, defined as four or more drinks on one occasion, according to the CDC. I’ll never know for sure, but all the drinking I did in my adolescence may have helped pave the way for the cancer I got at 47.” (My emphasis)

In other words, faced with highly restrictive laws and social attitudes, she displayed a kind of reaction formation that progressives often note when behaviors and substances are repressed. This argument is one they use, quite rightly, to argue for the decriminalization of a range of illegal substances.

But Mother Jones/Mencimer—along with liberals like Bruni, Biden and others who trace their hatred of drugs to their repugnance towards alcohol—aren’t opposed to cracking down in the case of alcohol.

Indeed, a common argument by drug policy reformers in favor of legalizing marijuana and decriminalizing other drugs is that cannabis and other substances are not as dangerous as alcohol. Lester Grinspoon, long-time marijuana legalization advocate, often argued that “no amount of research is going to prove that Cannabis [marijuana] is as dangerous as alcohol or tobacco.”

While the tactical convenience of this argument is easy to understand, its potential to backfire is equally evident. Do those who endorse it really want to make alcohol illegal, or to treat it more harshly than marijuana?

Temperance attitudes, which have caused this country such harm in one way and another, generalize readily from marijuana and drugs to alcohol and vice versa. Support for them in one area has a way of coming back to bite us in another.

Unsurprisingly, the Mormon Church is not an advocate for liberalized drug laws. In November, Utah considers medical marijuana in a ballot initiative. The Church opposes this humanitarian measure on the grounds that “the proposed Utah marijuana initiative would compromise the health and safety of Utah communities.”

This is the exact position taken by the Trump Administration’s Justice Department as it fights to resist and reverse drug policy reform. Indeed, lest you forget and think the current administration’s anti-marijuana stance is an aberration, recall how, in the Obama Administration, teetotaler Vice President Biden combined with non-drinking former Drug Czar Michael Botticelli to curtail marijuana policy reforms.

America remains steeped in Temperance attitudes. We are not well served by this aspect of our national heritage, one that hampers real progressive thinking as alcohol and drug problems increase. And too often, Temperance blinders prejudice those toward whom we most look for a crucial innovative vision.

*As I discuss here, the European Comparative Alcohol Study—the first systematic study of drinking patterns across Europe—found that “alcohol-related mortality (including cirrhosis) was substantially higher in Northern than Southern Europe: 18 versus 3 such deaths per 100,000 for men, 3 versus 0.5 for women.”

** Funnily enough, there is one notable exception to this rule: Utah, home state of Mother Jones’ Stephanie Mencimer, is both the healthiest and the most abstinent state in the union. Overall Mormon culture, if not abstinence, seemingly leads to exceedingly good health outcomes. On the other hand, there is a tendency in highly abstinent states like Utah for the smaller group of people who do drink, like Mencimer, to encounter worse drinking outcomes than elsewhere, because their drinking isn’t socially regulated.

Financial Disclosures and Bio

My life’s work has been to define addiction and its sources and to devise sensible approaches for addressing it, most recently through my online Life Process Program. My motivating belief is that we systematically exaggerate the effects of drugs and miss the impact of culture, setting and psychology in addictive experiences. This has led me to explore cultural influences on beliefs about the effects of alcohol and alcoholism, as I did in 1984 in “The Cultural Context of Psychological Approaches to Alcoholism” in American Psychologist.

In 1993, I published in the American Journal of Public Health “The Conflict Between Public Health Goals and the Temperance Mentality,” which detailed how the health benefits of alcohol had been ignored in the U.S. This article, as has been nearly all of my work, was self-funded. In 1999, Archie Brodsky and I were given unrestricted grants by the Distilled Spirits Council (DISCUS) and Wine Institute to assess psychosocial benefits of drinking, an investigation published in 2000 in Drug and Alcohol Dependence as “Exploring Psychological Benefits Associated with Moderate Alcohol Use.” The main benefit Archie and I identified was better cognitive functioning in older moderate drinkers relative to abstainers. This finding has since been affirmed by the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and a 2009 consortium of the Research Society on Alcoholism. Our research led me to organize the 1998 conference and 1999 volume, Alcohol and Pleasure: A Public Health Perspective, funded by the International Center for Alcohol Policies, an alcohol industry group.

I haven’t received funding of any sort from the alcohol industry for many years.